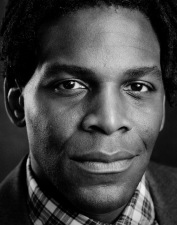

Lionel K. McPherson is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Tufts University. He has published on race (“Deflating ‘Race’,” J-APA), metaethics (“Normativity and the Rejection of Rationalism,” JPhil), war and terrorism (“Is Terrorism Distinctively Wrong?” Ethics), and global justice. He’s working on a book project, The Afterlife of Race, that develops the idea of socioancestry in place of “race,” the case for non-exclusionary Black political solidarity, and proposals for Black progress under officially race-neutral circumstances.

The Banality of White Supremacy (in and beyond Philosophy)

Lionel K. McPherson

Associate Professor, Tufts University

I’ve recently been thinking about what I call “the paradox of critiques of white supremacy.”

Here’s a critique that targets mainstream Western philosophy, courtesy of Meena Krishnamurthy:

“To the extent that white voices are privileged and challenges to white supremacy are not considered to be real philosophy, philosophy as it is traditionally conceived may itself be understood as an expression of white supremacy. We should decolonize philosophy….”

This way of putting the point shares a tendency to invoke “philosophy” without specifying a cultural provenance—which seems to assume either some unified conception of philosophy or the Western variety’s centrality.

Yet Western philosophy is not akin to an occupied territory: the tradition mainly occurs in (majority or plurality) white territories. Its history is a source of color-conscious cultural pride (recall Hume’s “There never was civilized nation of any other complexion than white, nor even any individual eminent in either action or speculation”). The updated notion of Western philosophy as a distinctive approach to critical reflection—with the use of reason, unbounded by established traditions, religious proclivities, political realities, and social identities, in search for Truth—has disappeared the affirmation of whiteness in its constitution.

Contemporary white supremacy has similarly moved toward declaring racelessness, despite all appearances to the contrary. Of course, critics of “white supremacy” believe that whiteness hasn’t gone anywhere: they use the term to refer to systemic, prevalent, unfair domination, exclusion, or absence of non-white peoples and their projects. What, then, could be the realistic prospects for non-white equality in white territories?

From what I can tell, we are to believe that a critical mass of white people might finally be convinced—500 years and counting in the land that became the United States, for example—by moral suasion or at least feelings of shame…to correct their territory’s practices of white supremacy. The same belief would apply to the practice of Western philosophy, with the added assumption that “we” are a mostly open-minded, enlightened, well-intentioned community.

That assumption seems optimistic. I’ll be less polite than Krishnamurthy: the Anglo-American philosophy profession has continued to be a proud site of white supremacy. To modify the duck test: If it looks like white supremacy, acts like white supremacy, and talks like white supremacy, then it probably is white supremacy. I’m only a self-appointed messenger. The United States, particularly in relation to Black Americans, is my territory of focus.

A perverse feature of American life is that calling a white person racist is allegedly a very wounding insult. Evidently, however, most White Americans still accommodate themselves to a country that looks, acts, and talks like white supremacy. As for the liberal precept “We shouldn’t speculate about what’s in a person’s heart, mind, or motives,” Black Americans cannot reasonably go on, without substantial evidence, suspending skepticism about the racial good faith of individuals.

A 15-minute Internet search will turn up countless studies and reports about glaring racial disparities in income and wealth, health, housing, education, employment, criminal justice, and police violence. Lack of access to information is no longer a plausible excuse for inaction, if it ever was. The shamelessness of mundane white ignorance can be literally frightening.

Most Black Americans have an anti-black bias sense (roughly analogous to “gaydar”). This sixth-sense, while imperfect, develops from inherited experience. The ability to distinguish vicious, indifferent, fake, and loyal white folks has long been crucial to black well-being (h/t Lucius Outlaw). Relatively few White Americans today seem viciously anti-black: they just don’t care enough about the lives of Black Americans to do or give up much, if anything, to correct anti-black injustice and inequality.

Post-Ferguson, hardly a week goes by without additional public evidence that the country is largely disinterested in any imperative of equal citizenship. Police killing of unarmed or non-threatening black persons is routine and willfully underdocumented. White America has been far more outraged about athletes kneeling in protest during the national anthem. Terror lynching is back for the 21st century, now usually state-sanctioned, with videos of anti-black brutality serving as modern-day lynching postcards.

For instance, the Ohio prosecutor who released a report that deemed 12-year-old Tamir Rice’s summary killing by police “objectively reasonable” did not expect to convince any sensible person who saw the video. The report flaunts white domination and anti-black disrespect, under the pretext of a credible investigation. We comprehend, explicitly or implicitly, the familiar message.

Black subjugation has been a pillar of white supremacy in America, not an anomaly that deforms the claim to equal citizenship. This reality is irreconcilable with national myth. Racial discrimination, bias, and disadvantage are acknowledged as problems “we” should address. “We” are supposed to include many White Americans—essentially good persons who would welcome substantive change. Somehow, though, the dream of approaching racial equality is perpetually deferred.

Herein lies the paradox of critiques of white supremacy. If “we” Americans had the power and conviction to bring about racial justice, we wouldn’t be close to where we are (by macro-level measures) almost 50 years after the Civil Rights Movement. Indeed, the idea of contemporary white supremacy evokes practices that are ostensibly “colorblind” and typically operate without self-consciously racist agents. These practices depend on day-to-day inertia and complicity. The conditions under which radical change might happen through dialogue, moral suasion, empathy, etc. do not appear to obtain: otherwise, white supremacy in America would have been well on its way out.

In short, “we” have been stuck in the banality of white supremacy.

Liberal versions of white supremacy always seek diversionary explanations for racial inequality. Attention is directed to “implicit bias,” with the quick addendum that everyone suffers from some forms of it to some extent; or the “pipeline problem,” whereby few, if any, suitable candidates can be found mainly because of unfortunate circumstances beyond the control or responsibility of white agency at whatever site; or the evolutionary-psychological basis of “tribal” race discrimination, never mind that most Black Americans are not monoracially black/African; or a simply “natural” preference to live and work with people who look (color-consciously) similar.

In general, white supremacy sets low baselines for “racial progress.” White America still insists on taking credit for ending slavery and Jim Crow. “We” are supposed to be optimistic since white feelings about black persons have changed for the better. The standard in Western philosophy departments, when Hume’s (or Kant’s or Hegel’s) profound racism does come up, is to immediately explain that he opposed slavery or that his alleged racism is irrelevant to this great mind and the respect due his central ideas, and thus “we” needn’t consider the issue further.

That “racial issues” may have important ramifications for “race-neutral” philosophical arguments is sometimes clear. Some of us balk at the ahistorical approach to property rights in Nozick’s celebrated Anarchy, State, and Utopia, with its virtual silence on slaves, their stolen labor, and the purported impossibility of reparations to their descendants. Nor will we be comforted by Rawls’s agenda-setting view that “we” must first complete “ideal theory” to adequately understand how to reform our non-ideal world. One needn’t be Black American for this to seem utterly implausible and impractical. Yet the lack of urgency to theorize racial justice is normal in the mainstream philosophical territory.

To reiterate, the Anglo-American philosophy profession, like the history of modern Western philosophy, has been a site of white supremacy, no matter its practitioners’ intentions. “White voices” are of course privileged. They have origin stories about how their people’s domination is almost entirely innocent or appropriate—whether due to the objective merits of their intellects, methods, interests, and values or to various factors external to the substance of philosophy and its cultural practice.

An obvious reason few Black American students venture into Western philosophy departments, with the few who do rarely sticking around, is that those places—with the faculty and other students, the questions taken to be worth pursuing, the often passive-aggressive atmosphere of discourse above the fray of distracting social justice movements—loudly pings their anti-black bias sense receptors. “We” philosophers are what we say and do for real, individually and collectively. Random “minority” lists, disingenuous affirmative “outreach” notices, and low-powered “diversity” initiatives do not inspire the suspension of disbelief. The awareness of being tolerated as a marginal outsider gets tiring.

This is what a kinder, gentler site of white supremacy feels like. From a macro perspective, the makeup of the Anglo-American philosophy profession looks nearly indistinguishable from its pre-1965 profile. Black students and professors represent no more than roughly two percent of the total constituency.

There is no solving white supremacy in defiant white territories. Incremental change is likely as good as it will get in America—from a people who, as the late spoken-word singer Gil Scott-Heron wryly observed, managed to put “Whitey on the moon,” within eight years of declaring the ambition a national priority.

Increasingly, the only persons fooled by contemporary white supremacy are those willing to accommodate themselves to it. But they remain an entrenched, critical mass, which is why racial justice or even decency cannot be approximated…until they decide to change.

Pingback: Anglo-American Philosophy: "A Site of White Supremacy" - Daily Nous